El Reino de Benín en África destruido por la colonización de los Ingleses – Ciudad Diseñada con geometría sagrada.

http://revealinghistories.org.uk/colonialism-and-the-expansion-of-empires/articles/the-empire-of-benin-and-its-cultural-heritage.html?utm_source=Charter+Cities+Institute&utm_campaign=403484598c-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_02_07_10_12&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_fccc97d8cc-403484598c-355516361

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/18/story-of-cities-5-benin-city-edo-nigeria-mighty-medieval-capital-lost-without-trace?utm_source=Charter+Cities+Institute&utm_campaign=403484598c-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_02_07_10_12&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_fccc97d8cc-403484598c-355516361

Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace.

With its mathematical layout and earthworks longer than the Great Wall of China, Benin City was one of the best planned cities in the world when London was a place of ‘thievery and murder’. So why is nothing left?

.

African fractals

Benin City’s planning and design was done according to careful rules of symmetry, proportionality and repetition now known as fractal design. The mathematician Ron Eglash, author of African Fractals – which examines the patterns underpinning architecture, art and design in many parts of Africa – notes that the city and its surrounding villages were purposely laid out to form perfect fractals, with similar shapes repeated in the rooms of each house, and the house itself, and the clusters of houses in the village in mathematically predictable patterns.

As he puts it: “When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganised and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet.”

At the centre of the city stood the king’s court, from which extended 30 very straight, broad streets, each about 120-ft wide. These main streets, which ran at right angles to each other, had underground drainage made of a sunken impluvium with an outlet to carry away storm water. Many narrower side and intersecting streets extended off them. In the middle of the streets were turf on which animals fed.

“Houses are built alongside the streets in good order, the one close to the other,” writes the 17th-century Dutch visitor Olfert Dapper. “Adorned with gables and steps … they are usually broad with long galleries inside, especially so in the case of the houses of the nobility, and divided into many rooms which are separated by walls made of red clay, very well erected.”

Dapper adds that wealthy residents kept these walls “as shiny and smooth by washing and rubbing as any wall in Holland can be made with chalk, and they are like mirrors. The upper storeys are made of the same sort of clay. Moreover, every house is provided with a well for the supply of fresh water”.

Family houses were divided into three sections: the central part was the husband’s quarters, looking towards the road; to the left the wives’ quarters (oderie), and to the right the young men’s quarters (yekogbe).

Daily street life in Benin City might have consisted of large crowds going though even larger streets, with people colourfully dressed – some in white, others in yellow, blue or green – and the city captains acting as judges to resolve lawsuits, moderating debates in the numerous galleries, and arbitrating petty conflicts in the markets.

The early foreign explorers’ descriptions of Benin City portrayed it as a place free of crime and hunger, with large streets and houses kept clean; a city filled with courteous, honest people, and run by a centralised and highly sophisticated bureaucracy.

The city was split into 11 divisions, each a smaller replication of the king’s court, comprising a sprawling series of compounds containing accommodation, workshops and public buildings – interconnected by innumerable doors and passageways, all richly decorated with the art that made Benin famous. The city was literally covered in it.

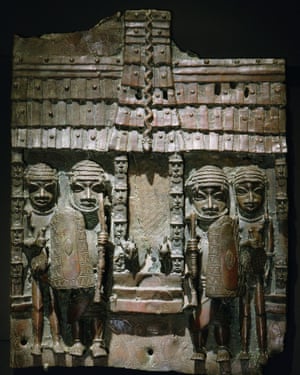

The exterior walls of the courts and compounds were decorated with horizontal ridge designs (agben) and clay carvings portraying animals, warriors and other symbols of power – the carvings would create contrasting patterns in the strong sunlight. Natural objects (pebbles or pieces of mica) were also pressed into the wet clay, while in the palaces, pillars were covered with bronze plaques illustrating the victories and deeds of former kings and nobles.

At the height of its greatness in the 12th century – well before the start of the European Renaissance – the kings and nobles of Benin City patronised craftsmen and lavished them with gifts and wealth, in return for their depiction of the kings’ and dignitaries’ great exploits in intricate bronze sculptures.

“These works from Benin are equal to the very finest examples of European casting technique,” wrote Professor Felix von Luschan, formerly of the Berlin Ethnological Museum. “Benvenuto Celini could not have cast them better, nor could anyone else before or after him. Technically, these bronzes represent the very highest possible achievement.”

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reino_de_Ben%C3%ADn

http://revealinghistories.org.uk/colonialism-and-the-expansion-of-empires/articles/the-empire-of-benin-and-its-cultural-heritage.html?utm_source=Charter+Cities+Institute&utm_campaign=403484598c-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_02_07_10_12&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_fccc97d8cc-403484598c-355516361